A well-written horror-themed resource management game with permadeath

Games focusing on villainous characters are fairly rare. Games that take this seriously are even rarer. Most games where you play an evil mastermind are comedic and cartoonish, like Evil Genius or Overlord. Thankfully Cultist Simulator, while cartoonish, is far from comedic. It approaches the topic of being the mastermind behind a cult as you would see in horror and supernatural fiction with a healthy dose of maturity and more imagination than you can shake a shoggoth at.

Released in 2018 as Weather Factory’s first title, Cultist Simulator is the brainchild of Alexis Kennedy, co-founder and writer of Failbetter Games, the studio responsible for Fallen London and the notorious nautical horror game, Sunless Sea. Cultist Simulator is atmospheric, and well-written, but suffers from some gameplay issues. It was also fairly bug-ridden for the first few months after release, but those bugs have mostly been patched out. The game has several DLCs out, mostly adding new characters to play as.

Gameplay

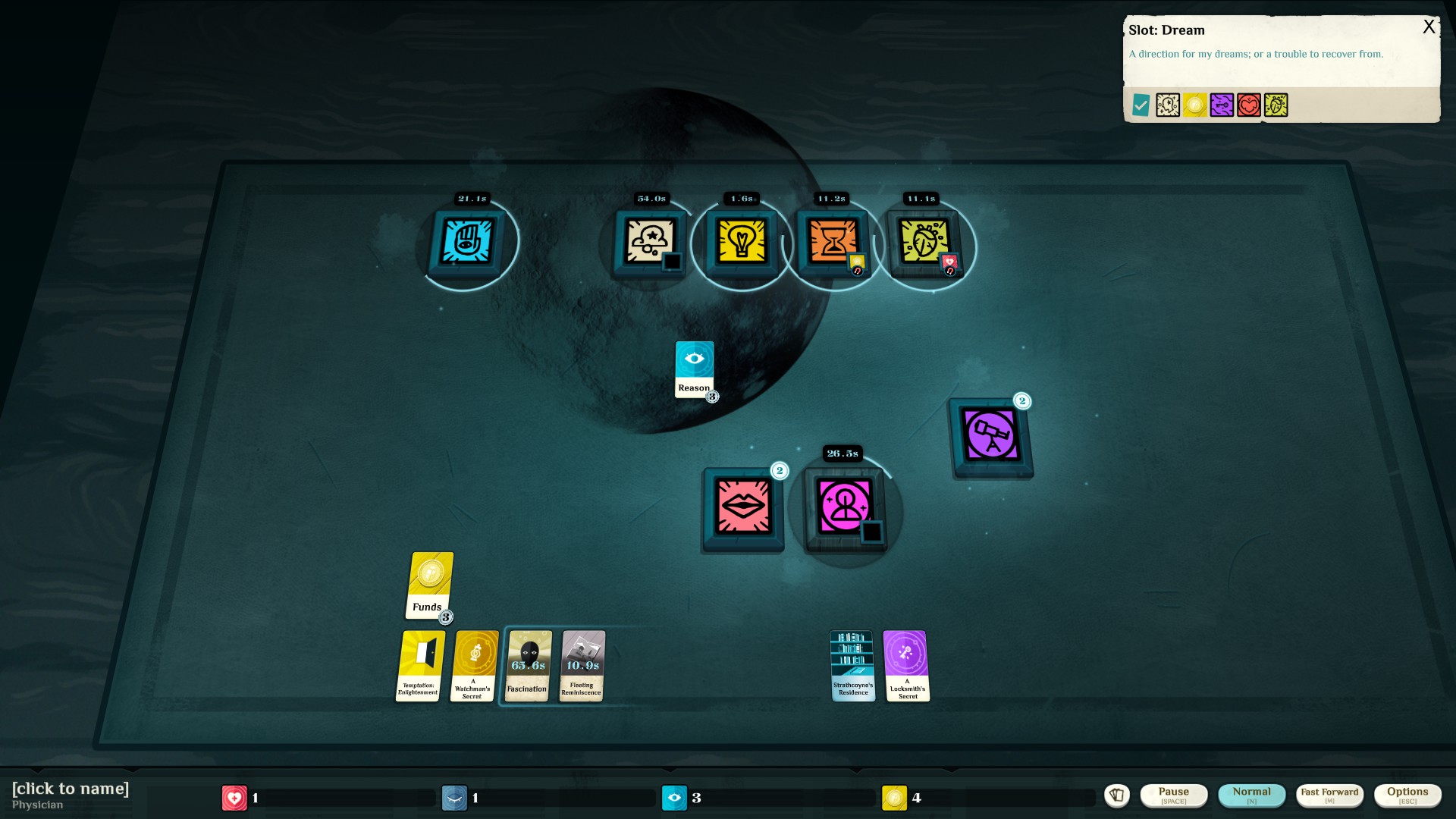

Cultist Simulator plays like a solo board game. You start with a couple of cards and events (or actions) with slots that can drag and drop them onto, which, in time, reward you with more and varied cards. You have cards denoting your main attributes: ‘health’, ‘reason’ and ‘passion’, cards for investigators and cultist minions, cards for the books and lore you uncover, and so on. These cards can be a bit abstract, so some imagination is required in their use. For example for the permanent ‘work’ event, using ‘health’ on this event will make you do manual labor, rewarding you with funds and sometimes vitality, which can be used to generate more health cards.

Unfortunately, working as a laborer can sometimes turn your health card into an injury card, preventing you from using that card until you treat it. If the timer on that injury card runs out before it’s treated, it will become a permanent ‘decrepitude’, effectively destroying a valuable health card. Instead you can get a nice, cushy office job that won’t give you injuries and takes ‘reason’ cards instead of health. On the downside, this sometimes requires more passion and mind cards than it says on the tin, as your abusive boss will force you to do overtime on the regular. Not working said office job for a couple of minutes will result in you losing it and having to waste a minute or so begging your boss to give your job back. If you’re not a fan of any of these options, you can use passion cards to make artworks, which usually requires a few more passion cards and a muse of some sort before you can actually make a living wage doing it.

Just like in real life, the tedious need to work is a compulsory part of the game. There’s a permanent ‘time passing’ event that regularly nicks your funds and will absorb health instead if you have no money. The sheer monotony of having to repeat this event every minute or so is probably a deliberate contrast to the many and varied cult activities you can undertake. It’s a clever way of reinforcing an underlying theme of escaping the drudgery of modern life into a (possibly delusional) world of supernatural intrigue, but it still makes the game something of a chore to play. The same goes for staving off other potential causes of death, such as depression and madness. Every now and then your activities will give you dread and fascination cards, which can give you a gameover if they build up too much. Early on, this felt like a big deal, and I struggled to find ways to counteract them. After working out how to reliably generate the cards that counteract these events, they became another part of the dull routine.

Advancing the goals of your cult generally requires sending your minions on expeditions to various locations of interest and overcoming the obstacles at these locations. Every minion, hireling and summoned spirit has a different spread of stats in several different kinds of ‘aspects’. Obstacles are overcome by sending the right minion to do the job. For example, to defeat the guardians of a warehouse that supposedly harbors some suspicious artifacts, you can either fight them by sending followers with the ‘edge’ aspect, or deceive them by sending followers with the ‘moth’ aspect. Your actual cultists generally start out with terrible stats, so it’s a good idea to pay for temporary hirelings to help out with your expeditions. For finishing an expedition you can get a mix of books, items and ritual ingredients. Books are generally the most important item as you can use them to generate scraps of lore, which are used to find your way through the dream world of ‘The Mansus’, among other things.

Every now and then, the tedium gives way to some interesting situations. For example, dealing with investigators and rivals is always fun, mostly due to the many options at your disposal. I ignored the weary detective building a case against me until he managed to get his hands on some strong evidence against me, at which point I realised that none of my minions were competent enough to sabotage the evidence. The detective ended up arresting and imprisoning one of my minions, and it was at that point that I decided I had to get rid of him. I remembered hearing that it’s possible to drive investigators insane by sharing higher level lore with them, so I tried that. Unfortunately, I must have used the wrong lore, as it backfired and the detective doubled down on his resolve and gained some bonus attributes, making him stronger than ever. I tried again and this time it sort of succeeded. I say ‘sort of’ because he decided to quit his job as a detective and became a rival cultist, which ended up working in my favour. He provided a welcome distraction for other detectives that turned up looking for me, and eventually ended up murdering one of them. Good job, Doug.

Aesthetically it looks like someone dropped a few too many paint cans on a Tim Burton set. The presentation is surprisingly colourful for such a morbidly themed game. The Mansus in particular looks fantastic as an abstract representation of a dream world. Every now and then, ghostly illustrations will slowly fade in and out of the board as certain events occur, sometimes to alert you to potentially threatening events that you’ll need to deal with. Overall the art style is fairly simple, but it’s consistent with the atmosphere and colours are often used to indicate what particular attributes some cards have, making it easier to find certain cards at a glance. The table that you have all the cards on could use a little more detail though. You spend all your time in the game staring at it, so it would nice to have some candles or books at the corners of the . Maybe a window to the outside world, where the view you have could be affected by the events currently occurring.

Story

That anecdote was also an example of how the narrative evolves based on your actions. You have a lot of actions available to resolve certain situations, and each one has consequences. You could summon a monster to kill a rival or investigator, but it might break free and eat one of your minions. You could start an affair with one of your cultists and then accidentally ignore them until they become disaffected and leave to start their own rival cult. The possibilities, while not endless, are at least plenty.

Your story begins simply enough: you work as a porter at a hospital and bond with an elderly patient. This patient soon passes away, leaving his belongings to you. Aside from a rather generous amount of funds, this includes some suspicious documents. Studying the documents piques your interest into the unknown by providing you with a scrap of lore from the ‘lantern’ aspect, which can be used to find your way to Dream World of the ‘Mansus’. From there you can find contacts which whom to found your cult and choose the founding principles (will you strive for power, enlightenment or something else?). From there, the game does a decent job at making you feel like a cult leader delving into the unknown as you translate antique books of obscure languages, trade this knowledge with interested patrons, and slowly piece the lore together into a deeper understanding of the complicated supernatural world that lurks beneath the surface of the game.

The specifics of the story – the how and what of your actions – are told eloquently through the prosaic shreds of information you find on the cards and events. The flavour text itself is both evocative and foreboding, while never quite revealing enough to dispel the mystique of the setting. This is an impressive achievement when considering the sheer amount of text in the game. The style of the writing is certainly reminiscent of H.P. Lovecraft, but lighter and not quite as verbose. Kennedy’s mastery of this particular style of writing is on full display in Cultist Simulator, as he deftly weaves a world full of strange spiritual intrigue and ambiguity while omitting just the right amount of detail so as to keep the setting from becoming mundane.

The setting itself is also inspired by Lovecraft, but moreso his Dunsany-inspired Dream Cycle series than the usual more depressing Cthulu Mythos suspects. There’s a surreal fantasy impression to most of the lore you uncover, and the dream world of the Mansus could have been ripped straight out of the one of the Dream Cycle stories and I wouldn’t have been able to tell. The ‘hours’ are basically the deities of the Cultist Simulator setting, and seem like the pantheon of gods from a high fantasy setting than the alien abberations of Lovecraft’s works. The more I learned about the Mansus and the Hours, the more I found it weirdly reminiscent of Garth Nix’s YA fantasy series, The Keys to the Kingdom. Kudos to anyone who actually read that.

Conclusion

My most recent run ended prematurely when I accidentally left the game running while I was away from the PC. Perhaps more disappointing than this is the fact that I don’t really feel inclined to try again. Usually roguelike games encourage replayability and experimentation by giving you the option to build different types of characters and include the allure of the randomly generated environments and items. In Cultist Simulator, the ability to use a variety of different cards to resolve events is what makes the game differ from playthrough to playthrough. However, none of these options feel like they change or mitigate the grindiness at the heart of the game. There’s not really any challenge to the game, aside from the initial learning curve of having to figure out how to not die to perfectly mundane events. The thought of having to painstakingly climb back up to where I was before was enough to keep me from wanting to replay it again and in turn makes it difficult to recommend.

The easiest way to solve this would be for the developers to add a way to automate certain actions, like constantly repeating your office job and having it automatically take the cards it needs if you work overtime. Unfortunately though, this has been a common suggestion from the community, and it doesn’t seem like the developers plan to implement a feature like this any time soon. To me it seems like the tedium is intended, but I honestly don’t think it really adds enough to the narrative for it to warrant making the game frustrating to play, especially since it has obligatory permadeath. This makes it difficult to recommend to anyone but hardcore fans of Lovecraft and gothic horror.

Overall Cultist Simulator is an interesting experimental title with exceptional writing and a fitting art direction hampered by a core gameplay loop that is mildly interesting at best and tedious at worst. If you’re willing to accept some compromised gameplay for an interesting narrative experience, go for it. If not, maybe pick it up when it’s in a humble bundle or below ten bucks on steam.